Plastic pollution has invaded life from the arctic to the equator. Vast amounts litter oceans, cities and beaches. Micro-sized plastic particles and minute fibres are accumulating in soils and sediments. Plastic is now in the air we breathe, the water we drink, the clothes we wear and the food we eat.

Plastic ubiquitous, insidious and impossible to avoid. Microscopic, potentially toxic particles and fibres, measuring the width of a human hair or less, have been found throughout the human food chain, in seafood, insects, shellfish, bottled, tap and well water and salt. Even enjoying a pint of beer, a soft drink, or a sweet treat containing honey and sugar might no longer be so carefree – or plastic-free - as you think.

The world’s oceans teem with far more debris than previously thought. Nearly all the pollution that ends up as minute pieces in water starts on land, leaching into rivers and onto beaches via degrading bags, bottles, and other plastic items, washing machines, sewers, overflows, waste dumps, incinerators, and industrial processes. These pathways require further mapping.

Breaking the Plastic Wave is a landmark report that explores these six pathways (or scenarios) and shows us there is no single solution for addressing the problem of plastic pollution in our ocean. The only route to clean and healthy seas is to address the problem systemically.

The report was prepared by The Pew Charitable Trusts and SYSTEMIQ, in partnership with Common Seas, the University of Oxford, the University of Leeds and the Ellen MacArthur Foundation. It was published in Science on the 23rd July 2020.

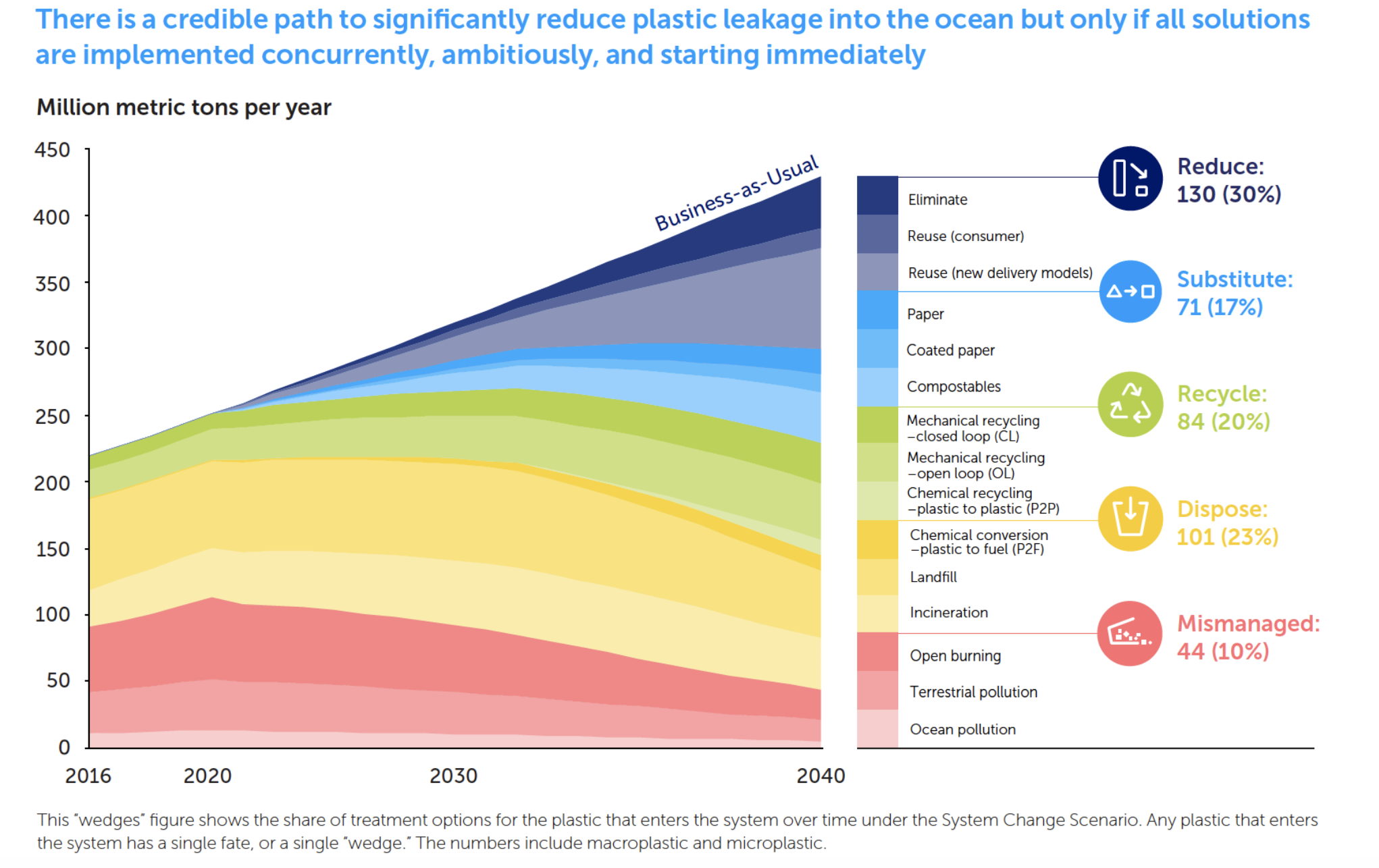

Breaking the Plastic Wave tells us more clearly than ever before how much plastic our world is producing, and how much of that is escaping into the environment (see below). Looking ahead to 2040, the report models different scenarios. As you might expect, a business-as-usual approach (where we continue as we are today) takes us to a grim future: a world in which we fail to meet our climate target to stay under 1.5 degree of warming and have an ocean full of plastic.

While most attention has been paid to plastic in the ocean, the reality is that everyone, from pregnant mothers and the unborn child, to old age pensioners and workers in rich and poor countries, is being contaminated to some extent – but the question remains, does this increase our chances of becoming ill?

Information about how plastics may be affecting human health is still limited but scientists are now calling for a complete rethink about how plastics are made and disposed of. Bigger, better, and more definitive studies are needed to investigate the toxic characteristics of micro-plastics, their behaviour in the human body and what constitutes a safe threshold for exposure when inhaled or eaten.

Breaking the Plastic Wave represents the most significant modelling of ocean plastic pollution to date, and it provides irrefutable evidence that we need to radically rethink how we make, use and dispose of plastic. Fortunately, as well as sounding a warning klaxon, the report offers both hope and a clear plan. In its own words:

“The report’s most important message is that, with the right level of action, tackling the problem of plastics pollution may be remembered as a success story on the human ability to rethink and rebuild systems that can sustainably support lives and livelihoods while the environment thrives.”

We can solve the plastic pollution crisis, and this report tells us how.

Plastic never goes away. The vast majority is nearly indestructible and lasts for hundreds, if not thousands of years. Under the action of waves, wind, oxygen, heat, ultraviolet light and friction, it simply fragments and breaks down into smaller and smaller particles.

As the global economy expands, its use escalates and human exposure to micro plastics grows. Since the 1950s when plastics were first mass-produced, an estimated 8.3 billion tonnes have been manufactured of which nearly 80% is believed to have been landfilled or to be still in the natural environment. Production increases about 3% a year and is forecast to double again in the next 30 years, by which time another 30 billion more tonnes may be manufactured annually

Our appetite for plastic is insatiable. One million plastic water bottles are bought around the world every minute and that number is expected to jump another 20% by 2021. Plastic may last for generations, but nearly half of all that is made becomes waste within four years, 40% has only a single use and 90% is not recycled. Up to 12 million tons of plastic litter could be entering the ocean every year and the amount is set to triple by 2025.

Most plastic is produced in rich countries, but the majority of pollution comes from the many countries that have poor or non-existent collection and recycling systems.

Plastic debris may be a modern scourge yet its versatility and benefits are unquestionable. Over the last 50 years, it has fuelled the global economy, become the packaging material of choice and is used in a myriad of manufacturing processes. It is found in adhesives, paints and cosmetics, cars and electronics, cables, computers, dry-cleaning fluids, rocket fuel, roofs, tanks, and insulation, toys, furniture and many construction materials. The durability and adaptability of this petrochemical product has made it the true child of the oil age.

Most plastic is produced in rich countries, but the majority of pollution comes from the many countries that have poor or non-existent collection and recycling systems. The result is not just ocean pollution but a tsunami of plastic litter clogging drains, causing floods and becoming ideal breeding grounds for mosquitoes. Eight Asian and two African rivers, including the Yangtze, Indus, Nile and Ganges, are thought to transport nearly 80% of the world’s microplastics to the World’s oceans.

Plastics are made from a broad range of chemicals known as polymers which are 99% derived from the oil and gas industry. Synthetic, or man-made, chemicals are then added in the manufacturing process to this feedstock to give plastic qualities like strength, flexibility, durability, colour and transparency.

The combination of these polymers and added catalysts, stabilisers, pigments, flame retardants and solvents, results in a cocktail of contaminants which not only alter the nature of plastic but can leach as toxins into the air, water, food and human body tissue.

Marine life has been widely seen to be devastated by large bits of floating plastic. Humans, however, are likely being increasingly exposed to micro and nano-sized plastic particles and beads. These are predicted to be consumed by ingesting them in food and drink; by absorbing them through the skin; and from potentially inhaling them. Whatever way, the result is the growing presence in the human body of toxic chemicals.

Scientists know that microplastic particles can absorb or carry organic contaminants, such as PCBs, pesticides, flame retardants and hormone-disrupting compounds. But the risks they pose is unclear and not uniform. Some particles may pass quickly through the human body without releasing their toxins, others can accumulate in it but be harmless, more still may remain lodged in the body in dangerous concentrations. The most dangerous could be the smallest nano-particles which can enter cells.

What is certain is that many of the chemicals that are routinely used to make plastic are dangerous. Bisphenol A (BPA), a group called phthalates, and some of the brominated flame retardants, all of which are used to make household products and food packaging, are proven endocrine disruptors which can damage human health if ingested or inhaled ,.

Some of these toxicants have been linked to cancers and damage to the immune system. Others have been shown to travel across a mother’s placenta and be particularly dangerous to young children. Many have been banned from use in baby bottles and children's toys. Others in regular use have been linked to the malformation of foetuses and adverse birth outcomes, as well as allergies and cardiovascular disease. Many of the additives to plastics have been studied, but the hazards of minute plastic particles to humans are only slowly emerging.

If we commit to system change, we can reduce the plastic flowing into the ocean by 80% (compared to business as usual) using technologies and approaches that are already available to us. As well as reducing the impact on our ocean, system change generates savings of $70 billion for governments over the next twenty years. It also reduces projected greenhouse gases by 30% and creates at least 700,000 jobs. In the report’s own words:

“Addressing plastic leakage into the ocean under the System Change Scenario has many co-benefits for climate, health, jobs, working conditions, and the environment, thus contributing to many of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.”

Changing the system doesn’t mean we lose all the important and useful products and services plastic provides. In fact, we can meet 2040’s anticipated global demand for ‘plastic utility’ with about the same amount of plastic that’s being used today. This means we can decouple plastic growth from economic growth, which is vital for a sustainable future.

Time is of the essence. A delay of five years will result in another ~80 million metric tons of plastic going into the ocean by 2040. Read on to see how we’re working on the ground today to deliver change.

Microplastics have been reported in varying amounts in many species of seafood as well as in sea salt, honey, sugar, and processed food and drinks. They can enter the food chain via water, contact with food packaging, air pollution in shops, homes and food factories, and via sewage sludge which is spread on fields as a fertiliser.

Micro- and even smaller nano-plastics get into the human food chain via sea foods which for millions of people are essential to diets. Microplastics have been found in cod, mackerel, sea bass and more than a quarter of fish in markets in Indonesia and California.

But micro-plastics have been found in much larger quantities in many other marine organisms including zooplankton, crustaceans and shellfish. Concern is growing over the 22 million tonnes of bivalves which humans eat each year. These oysters, mussels, clams, shrimps and scallops use their gills to filter and capture tiny particles of food in the water such as phytoplankton, and so are in permanent contact with plastic-polluted water.

Belgian scientists recently calculated that shellfish lovers are eating up to 11,000 plastic fragments in their seafood each year. In China, where much of the world’s shellfish is farmed and eaten, and where much of the micro plastic pollution has been found, consumers are thought to ingest ten times as much.

Plastics can also contaminate the human food chain through constant exposure to the chemicals used in food packaging, building and household materials.

Many of the most widely used plastics in packaging contain a group of chemicals called Phthalates and BPA (bisphenol A). These key compounds of polycarbonate and polyester help soften plastics and make them transparent. BPA is used to make water bottles, coat the inside of food tins, line bottle tops, food trays and water pipes.

But researchers have shown how BPA and other chemicals have been detected widely in urine samples, leach into foods and are linked to asthma, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, breast cancer, obesity and type II diabetes.

The US national Toxicology programme (NTP) says it has “some concern” for BPA’s effects on the brain, behaviour, and prostate gland in foetuses, infants, and children.

Research is based largely on animal studies and no single study conclusively proves that BPA is harmful to humans , , but the danger of people chronically poisoning themselves is taken seriously by some governments and many scientists. The US national Toxicology programme (NTP) says it has “some concern” for BPA’s effects on the brain, behaviour, and prostate gland in foetuses, infants, and children. It is still used widely in Britain in food containers.

Phthalates are a large class of chemicals that are widely used in shampoos, lipsticks, drugs, flooring, plasticisers, food packaging, toys, and cosmetics. Few have been fully studied, some have been banned and their cumulative toxic effect on humans is unknown. However, in the past few years, researchers have linked phthalates to asthma, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, breast cancer, obesity and type II diabetes, low IQ, neurodevelopmental issues, behavioural issues, autism spectrum disorders, altered reproductive development and male fertility issues.

The fear is that micro plastic particles are carriers for other toxins to enter the body. Plastic microparticles are known to bind to compounds containing toxic metals like mercury, and organic pollutants including pesticides, and chemicals called dioxins known to cause cancer and reproductive and developmental problems. If the microparticles enter the body, these toxins could then accumulate in fatty tissues.

Earlier this year the River Tame in Manchester was found to have 517,000 plastic particles of plastic per cubic metre of sediment, nearly double the highest concentration ever measured anywhere else in the world. Yet the industrial river which flows into the Mersey and then the Irish sea is widely thought to be one of the most ecologically improved in Britain, full of fish and inspected regularly by the Environment Agency.

Microplastic pollution is turning up in “fresh” water everywhere around the world. Particles have been found in bottled and tap water, well water and 24 varieties of German beer. The more researchers look, the more they are finding.

Several recent studies have shown drinking water to be contaminated with microplastics. In one, 159 us tap water samples were taken from seven counties and 94% were found to be contaminated. Some contained up to 57 micro particles per litre. The authors concluded that people may consume 3-4,000 particles a year from tap water alone.